Microplastics Have Now Been Found in Testicles. How Bad Is That?

Evidence shows microplastics can end up in many different organs and may harm reproductive health

Reproduction

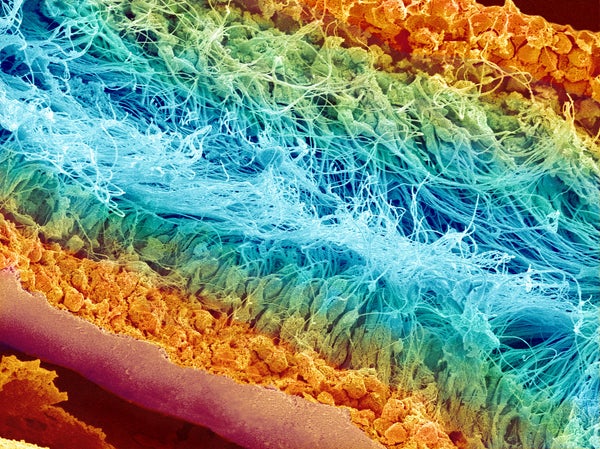

Microplastics are everywhere. These tiny polymers, shed by the 400 million-some metric tons of plastic that humans produce each year, are in the food we eat and the water we drink—and therefore our body. While microplastics’ impacts on human health have not yet been fully established, evidence suggests chemicals in some plastics can disrupt hormone signaling, potentially leading to a wide array of health effects.

New research is painting an increasingly concerning picture of how microplastics may be impacting our reproductive health. In a study published last week in Toxicological Sciences, researchers tested 23 human testicles and 47 dog testicles and found microplastics in every sample. They also found that dog testes with higher concentrations of certain microplastics tended to have lower sperm counts. The findings add to previous work that showed that other reproductive organs are also affected—a study published in February found microplastics in all tested samples from the human placenta, the temporary organ that feeds oxygen and nutrients to a developing fetus.

“There hasn’t been a body part that people have looked but haven’t found [microplastics] in,” says Tracey Woodruff, an environmental health researcher and director of the Program on Reproductive Health and the Environment at the University of California, San Francisco. Her research and that of others have found that these plastic fragments can harm human health. “It’s not a stretch to think that we’re just going to find more adverse health effects with microplastics,” she says.

Scientific American spoke with Woodruff about how microplastics impact our reproductive organs and what, if anything, we can do about the problem.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

Did it surprise you to see that researchers found microplastics in human testicles?

Yes and no. I mean, they have been found in seminal fluid, the placenta, stool, blood and breast milk…. So it’s kind of surprising but also to be expected given everyplace else that they have been found. Also, it makes sense because chemical companies are producing so much plastic—it’s doubled in production since 2000 and is projected to triple by 2060.

How do microplastics get into our body? Is it just through eating and drinking?

Drinking, eating and breathing—for example, microplastics are generated from car tires, so they can get in the air, and then people can breathe them.

How do they get into the testicles?

Well, I think that they’re traveling around the body in your blood. Some of these particles are very, very small. With all of the places in your body that are being supplied by your blood, it’s an opportunity for [microplastics] to diffuse into different tissues.

Would we expect to find microplastics in ovaries, too, or are they different somehow?

Oh, no, I think we would expect to see them in the ovaries if we measured them.

The new study found that dog testes with higher concentrations of certain microplastics had lower sperm counts, but these observations can’t prove a causal link. How might microplastics harm reproductive health?

The developmental period—the fetal period through early childhood, when your reproductive systems are developing and growing—is a harmful period for exposure to chemicals, particularly endocrine disruptors [such as microplastics]. In a systematic review of the evidence, which my colleagues and I conducted in 2022, our conclusion was that microplastics are suspected to be a reproductive toxicant [a substance that impacts fertility] and to increase the risk of cancer—especially in the digestive system. That conclusion is based on animal experiments—researchers randomize the animals, expose them to different amounts of microplastics and measure the effects. The effects this new study found on sperm are very similar to the effects we saw in the rat and mice studies that were done earlier. So there’s some cause for concern.

How can people limit their exposure to microplastics?

Don’t microwave food in plastic. Reduce your use of plastic water bottles and other types of plastic containers. In the new study, the humans had three times more plastic in their testicles than the dogs did. That could be because humans are doing more things that expose them to plastics—for example, drinking out of plastic water bottles. We know dogs aren’t doing that, and maybe the disparity in the amount of microplastic is a reflection of that difference.

There have been a lot of studies on chemicals added to plastics called phthalates, which we’re primarily exposed to from contaminated food. These show that if you eat less food prepared outside the home, you can reduce your exposures to phthalates, so I would anticipate that that would be true for microplastics as well.

I microwaved plastic at lunch today, so I’m not feeling great about that decision.

Then look at the health benefit you can get right away—you won’t do that tomorrow!

Also, you can take personal action, for sure, but we can take [collective] actions now to mitigate these health effects. We don’t need more plastic—we have plenty of it in our life. There are currently international treaty negotiations around plastic—so we could decrease plastic production. And the government could start looking into both evaluating the health impacts of microplastics and implementing regulatory strategies to mitigate harmful exposures.

What could the U.S. government do to curb plastic use?

Microplastics could be evaluated [by the Environmental Protection Agency] under the Toxic Substances Control Act. Vinyl chloride [which is used to make PVC, one of the plastics that the study found in testes], is one of the chemicals EPA is currently evaluating under this act. The EPA could consider exposures to vinyl chloride as a microplastic in its risk evaluation and risk management rules to really lower harmful exposures.

It’s an opportunity. We could change the course and become healthier. Regulations are a great driver of innovation. And the thing about plastics is that their source is fossil fuels. We have to reduce fossil fuel use anyway to address climate change—why not also stop companies from turning it into plastic? In the coming years we don’t want to be dealing with the consequences of microplastics, just as we are currently dealing with [the consequences of] climate change.

ALLISON PARSHALL is an associate news editor at Scientific American who often covers biology, health, technology and physics. She edits the magazine’s Contributors column and has previously edited the Advances section. As a multimedia journalist, Parshall contributes to Scientific American‘s podcast Science Quickly. Her work includes a three-part miniseries on music-making artificial intelligence. Her work has also appeared in Quanta Magazine and Inverse. Parshall graduated from New York University’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute with a master’s degree in science, health and environmental reporting. She has a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Georgetown University. Follow Parshall on X (formerly Twitter) @parshallison

whatseatingyoukid.club BPA and Microplastics Monster