A growing number of farms are seeking out pollinator-friendly certifications, but the two programs offering certification—run by the Xerces Society and Pollinator Partnership—are taking very different approaches.

BY TWILIGHT GREENAWAY AND CINNAMON JANZER

OCTOBER 17, 2022

Farmer Doug Crabtree walks in his sunflower field (Photo by Jennifer Hopwood, Xerces Society)

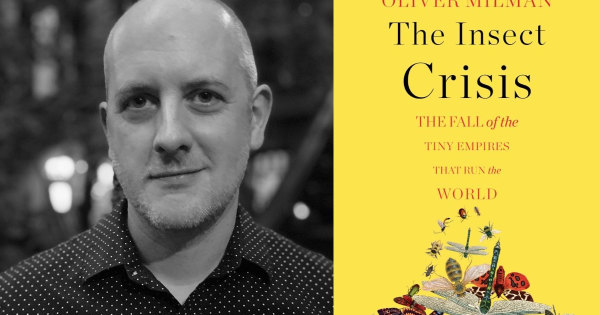

How Extreme Heat Puts Pollinators—and Crops—at Risk

What the Insect Crisis Means for Food, Farming—and Humanity

Far North Spirits, the northernmost farm and distillery in the contiguous United States, grows the rye for its whiskey and distills it on the farm. Just 25 miles south of Minnesota’s border with Canada, the farm’s fields of golden rye and heirloom corn are interspersed with highbush cranberry shrubs, bushy crabapple and plum trees, native grasses, and a growing number of bees, butterflies, and other pollinators.

Those plants—and the pollinators they feed—have been there since long before Far North’s owners Mike Swanson and Cheri Reese took over Swanson’s family farm and built a distillery in 2013. But this year, they decided to start making their presence known to their customers by applying for a Bee Friendly Farm designation from Pollinator Partnership, a national nonprofit dedicated to protecting and promoting pollinators and the ecosystems they rely on.

“Pollinated foods are some of our most nutrient-rich foods, some of our most colorful, and flavorful.”

For one, says Swanson, pollinators provide a lively entry point for talking with his customers about the way he and Reese run the farming part of their operation.

“Soil health, ecological diversity, sustainable ecosystems—all these things are very important to us. But I wanted a way to talk to people about what was going to be interesting to them,” he says. “When you’re talking about bees, that tends to pique people’s interest a little better. So, we’re able to talk about farming without talking about farming.”

Swanson is not alone in seeing the abundance of bees and other pollinators on his farm as a selling point, and a way to get his customers’ attention.

In fact, Americans are increasingly focused on pollinators, and they’re concerned about their well-being. In 2017, a survey found that 69 percent of respondents said they recognized pollinator populations are in decline and that number has likely grown as the news of the larger insect apocalypse—science that shows rapid decline in insect populations around the world—has been widely reported since then. In 2019, another survey found that 95 percent of respondents said they want to see designated areas where plants support pollinator health.

Pollinators are critical to food production: More than 80 percent of the world’s flowering plants—and around one third of the food crops—require a pollinator. And while it’s not clear exactly how many people are considering the plight of pollinators when buying groceries, a 2015 study found that use of the term ‘‘bee-friendly’’ had more economic value than other claims that advertised the absence of pesticides. And another study in 2018 found that consumers were willing to pay more (51 cents per dry liter) to buy blueberries and cranberries farmed in a way that supports wild pollinators.

Cal Giant Blueberries bearing the Bee Better Certified label. (Courtesy Xerces Society)

“Pollinated foods are some of our most nutrient-rich foods, some of our most colorful, and flavorful,” says Liz Robertson, who helps oversee the Xerces Society’s Bee Better Certified, another certification farmers are now seeking out. “There are wind-pollinated crops out there, but the nutrient-rich diet really depends on these animal-pollinated crops. And just over the last several decades, and increasingly in the last couple of years, there has been this real awareness and research on the decline of insects globally.”

All these factors explain why pollinator certifications have begun to appear in a growing number of grocery stores and corporate sustainability reports. The Bee Better seal is showing up on products sold by certified farms as well as on those from companies sourcing ingredients from those farms, says Robertson. Silk, Häagen-Dazs, and Cal Giant Farms are just a few of the brands that have sported the seal so far. Meanwhile, Pollinator Partnership’s Bee Friendly logo has appeared on a signature wine from Francis Ford Coppola Winery, and may soon make its way to more packaging.

Yet while the Bee Better and Bee Friendly certifications offer up similar wordplay, and similar stated goals—both want to see more diverse and flowering forage plants on farm landscapes and less pesticide exposure for pollinators—they are markedly different in multiple ways. One is reaching a smaller number of farms with a stringent, third-party certification, while the other is aiming for much larger adoption, especially among conventional farmers, and is asking less of participating farms by design.

Taken together, however, the two certifications provide a glimpse of some of the benefits —and the limitations—of using pollinator health to gauge the overall sustainability of a farm.

Planting pollinator habitat at the Jordan Winery Estate. (Photo courtesy of Pollinator Partnership)

The Certifications

The Bee Friendly Certification began as a local initiative in northern California’s Sonoma County that helped beekeepers find farms where it was safe to store their bees. Pollinator Partnership acquired it in 2013, but Miles Dakin, the current Bee Friendly Farming coordinator, says it wasn’t a big part of the organization’s work until around 2019, the year the Almond Board of California—the group that represent 7,600 almond farms on an estimated 1.6 million acres—reached out to the organization and initiated a partnership.

The Central Valley’s almond orchards rely heavily on millions of honeybees that are trucked in from the Midwest every spring—and many beekeepers have seen record-setting bee losses in recent years. As a result, the almond industry has moved to improve its image in the eyes of consumers.

“They really wanted to educate their growers and bring the industry in on bee-friendly practices,” says Dakin, who had studied integrated pest management (IPM) in the almond industry before taking the job.

Dakin was hired in 2020 and has been working with farms in California and across the country since, helping farmers add bee-friendly forage and habitat to their land and certifying around 250,000 acres of farmland and in the last two years. “We’re definitely expanding,” he told Civil Eats. “We have avocados, coffee, a whole bunch of different systems now certified.”

The Bee Friendly Certified program requires growers to pay $45, prove that they have forage “providing good nutrition for bees” (or are planning to plant it) on 3 percent of their land, as well as nesting habitat and water. They also must use Integrated Pest Management (IPM), a wide range of practices that can involve replacing pesticides with pheromones or simply identifying the location of pests before spraying to ensure that the application is targeted.

“We were already above and beyond the certification standards, so it wasn’t hard at all for us.”

Once they are on board, Dakin says, “every three years, the growers have to provide us with compliance documents, and we review those.” He also conducts field visits on 6 percent of the farms every year.

“We’re not a prescriptive program,” he added. “We don’t tell them what to do or how to do it. We give them the criteria, and we help them meet that criteria in the way that works for them.”

Farms that receive Xerces’ Bee Better Certification, on the other hand, are independently audited and verified by Oregon Tilth, an organic certifier that has been in business since 1975.

Even before the certification launched, the Xerces Society had been working with the agricultural industry, both directly with larger brands and their supply chains as well as through the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service to help farmers to install pollinator habitat and engage pollinator-friendly practices such as pesticide mitigation on their farms, says Xerces’ Robertson. “The farmers who were doing the work were like, ‘How do we communicate this to consumers?’”

She adds that the certification’s parameters are grounded in peer-reviewed scientific research done by Xerces and other institutions that looks at everything from the best native plant compositions for pollinators to the impact of pesticide drift.

We’ll bring the news to you.

Get the weekly Civil Eats newsletter, delivered to your inbox.

To date, Bee Better has certified more than 20,000 acres of farmland in the U.S., Canada, and Peru, with more applications in progress. Almonds are also a major crop for the certification, as are blueberries. Xerces is also in the process of bringing more certifiers on board so they can begin certifying farms in more countries.

In order to earn Bee Better Certification, farms must maintain pollinator habitat on at least 5 percent of the farm, and 1 percent of that habitat needs to be permanent year-round, meaning things like trees, hedgerows, and riparian corridors that include native plants. The certification also requires a “rigorous pest management strategy” that includes non-chemical practices as a first line of defense, targeted pesticide use, and limiting or eliminating the use of what Xerces calls high risk pesticide applications.

Changes on the Farm

For some farms, achieving pollinator-friendly certification is mainly a matter of documenting what’s already taking place. For instance, Klickitat Canyon Winery in Lyle, Washington, has long invested in planting native wildflowers and grasses throughout its vineyard and owner Kiva Dobson had already received organic certification prior to adding Bee Better certification to the list. “We were already above and beyond the certification standards, so it wasn’t hard at all for us,” says Dobson. Plus, “for every bottle [of wine] we sell, a percentage of that goes towards buying native plants, so [the cost] is integrated into our business model.”

Ceanothus serves as pollinator habitat on the Klickitat Canyon Winery. (Photo courtesy of Xerces Society)

But for the larger, conventional growers who sign up, pollination certification may require undertaking a paradigm shift.

Take Woolf Farming, a more than 20,000-acre, vertically integrated farming company based in Fresno, California, that grows a wide variety of crops, including massive tracts of almonds, pistachios, and canning tomatoes all over the state. Peter Allbright, the crop manager at Woolf Farming, says a business partnership spurred them to pursue Xerces’ Bee Better certification back in 2016.

“One of our almond customers is a very progressive European food company,” says Allbright. “They wanted us to look into pollinator habitat developments and that kind of thing, and they pushed us to work with the Xerces Society, so we were actually one of the first growers of theirs to be certified.”

Woolf Farming still has 3,000 Bee Better-certified almond acres, but the company has since chosen to put more than 7,000 additional acres of almonds into Pollinator Partnership’s Bee Friendly Farming program because, Allbright says, it’s much easier. Bee Better certification requires regular, multi-hour inspections that he describes as “more in-depth than an organic inspection” and maintains “a packet—a hefty list of rules.”

On top of the certification cost itself, Allbright says that planting pollinator-friendly habitat has also cost the company “well over a quarter million dollars in the last couple of years,” between buying the pants, irrigating them, and paying workers to weed them.

“Once [the habitat] gets established, it’s fine. It’s doable, but it’s extremely expensive to implement the Bee Better program,” added Allbright.

He says Pollinator Partnership’s Bee Friendly program has been much more flexible about where he can plant the additional habitat (they don’t require that it be in or near the almond orchard, for instance). And when a pest infestation looked like it could cut the almond crop on one of the farm’s properties a few years back, he says he struggled to get Xerces to make an exception that would allow him to spray approved pesticides aerially. Bee Better eventually made an exception, but he found the process frustrating. “Xerces is the gold standard. But you can’t blanket that across every acre of almonds in California,” added Allbright. “It’s not compatible. Hence, we haven’t done it on all of our acres.”

Pollinator Partnership, on the other hand, requires “minor bits of documentation to demonstrate that you’re not spraying insecticides during the almond bloom, those kinds of very common-sense things that most growers are already doing,” adds Allbright. He’s also concerned that Xerces, on the other hand, is so focused on supporting wild bumblebees and other wild pollinators that they may not always be looking out for farmers like him. As a conservation group, he added “They’re actively behind the scenes working against production agriculture.”

A metallic green sweat bee. (Photo by Amber Barnes, courtesy of Pollinator Partnership)

The fact that the organization advocated for the protection of wild bumblebees in California under the state’s Endangered Species Act—and that advocacy may have had an impact on the recent decision by the California Supreme Court to allow new protections for the pollinators—is one example that concerns Allbright. He believes the change will “severely impact almond production, because that really eliminates a lot of the tools we have for crop protection.”

However, Eric Lee-Mäder, an apple and seed crop farmer and the pollinator and agricultural biodiversity co-director at Xerces, says there’s nothing behind the scenes about the group’s work. “Xerces and other stakeholders have been open and transparent in examining the decline of California’s wild bumble bees precisely so the ag sector isn’t caught off guard. Ultimately the bees in question mostly do not even occur in agricultural areas.”

Dialing in on Pesticides

Research has found that adding habitat, cover crops, and more plant diversity overall to large monocrop operations can—over time—reduce the need for insecticides and other pesticides. And that appears to be the idea that both pollinator certifications are working with, albeit to different degrees. But asking farmers to intentionally spray fewer pesticides in the process is another thing altogether—and can be seen by growers like Allbright as an assault on their very viability.

“We don’t ban specific active ingredients in pesticides, because to us, it’s more about integrative pest management, about the mindset behind using the chemicals,” says Pollinator Partnership’s Dakin, who says IPM can greatly reduce pesticide exposure to pollinators when done right.

“The goal is still to reduce or even eliminate chemicals in general, but what we’re trying not to do is make something that’s not achievable by most of agriculture.” If you eliminate specific chemicals, he adds “it actually closes the doors for a lot of farmers.” Instead, Dakin says the organization wants to have all farmers at the table, and even some pesticide producers.

In the latest example of the latter, Pollinator Partnership is partnering with Bayer Crop Science (the company that bought Monsanto in 2016, making it the world’s largest pesticide and seed company) and other local entities in a $1.7 million project with the USDA to “improve pollinator habitat and forage across California’s agricultural landscapes.”

Today’s food system is complex.

Invest in nonprofit journalism that tells the whole story.

These kinds of partnerships are far from unusual for Pollinator Partnership, which also founded and runs the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign, a large collaborative body that includes 170 scientists, researchers, and government entities, alongside Bayer and CropLife America, a trade group that represents manufacturers of pesticides and other agricultural chemicals.

In another example, Pollinator Partnership has initiated research a few years back into the toxicity of the dust that’s released by pesticide-treated corn seeds that received funding from Bayer Crop Science, BASF, and Syngenta—the very companies that manufacture the seed-coating pesticides that cause the dust at the heart of the research.

“Having worked with many, many farmers over the years, it’s like people are on this pesticide treadmill and can’t get off; they can’t see their way out of it.”

Xerces Society has also engaged the pesticide industry in dialogue over the years. However, says Lee-Mäder: “We’ve never taken pesticide money as an organization. We never would, and we would never plant habitat or create pollinator conservation features where we feel there’s a potential risk to counteract the work we’re trying to do.”

But that doesn’t necessarily make it easier to work with farmers on pesticides. And Lee-Mäder and Robertson acknowledge that, like Allbright, not everyone they work with is eager to change their practices when it comes to pesticide use.

“We don’t always have the leverage to change pesticide practices. But it’s something that we stay pretty laser-focused on,” said Lee-Mäder. “And we constantly make that part of the dialogue with the grower. Bee Better does provide really clear sideboards on what you can and can’t do. But outside of Bee Better I think [Xerces] is constantly making judgment calls about what we’re comfortable with and what we’re not.”

Willa Childress, who leads state-to-state policy organizing work at Pesticide Action Network, compares working on pollinator habitat with large conventional farms to harm reduction, a strategy that acknowledges that making systemwide changes can be difficult, and many farmers need to be met where they’re at if they’re going to begin to change entrenched patterns and practices.

But exactly where they’re at doesn’t always allow for a shift. “Having worked with many, many farmers over the years, it’s like people are on this pesticide treadmill and can’t get off; they can’t see their way out of it,” Childress said. “And they encounter challenges even when trying to move slightly away, because they’re already bought into a system and have all their acreage in [conventional] agriculture.”

Childress says she’s seen a number of examples in the policy arena where the focus on getting more habitat in the ground is politically much more palatable than reducing pesticide use.

“We’ve seen this approach over and over again, which is to separate these different impacts that we know are contributing towards huge pollinator and other insect declines: pesticide use, lack of habitat, and disease,” says Childress. “Policymakers and different constituents have tried to pry apart the three pieces of this problem and the result is that we’ve passed lots of legislation trying to address increased habitat. And yet we haven’t seen a measurable difference in how pollinators are faring.”

The pesticide industry has such a powerful lobbying presence all around the country, says Childress, that bills calling for reduction in pesticide use rarely make it very far. “Our legislation isn’t matching up to our science, and the only reason can be corporate control of agriculture and corporate influence,” she adds.

When asked directly, Allbright said he hadn’t reduced his pesticide use at all—and it’s clear that he doesn’t see that as a goal either on the land certified by Xerces’ Bee Better nor the land certified by Pollinator Partnership’s Bee Friendly program.

For Xerces’ Robertson, the hope is to reach a productive, if sometimes challenging, middle ground. “If you look at the two ends of the spectrum, you’re going to have a certification that is so incredibly rigorous that nobody adopts it. Then you’re not moving the needle at all,” she says. “On the other side, you can have a certification that is easy and anyone can adopt it without changing their practices. So again, the needle isn’t moving. Our goal is always conservation and we’re always evaluating where we’re at and adjusting and weighing in on: Can we get farms to nudge and move the needle and adopt these practices? And are we matching with the science that says, ‘This is what has to be done to help curb the biodiversity loss we’re seeing?’”

For Far North Spirits’ Mike Swanson, even the less-stringent Bee Friendly certification is an important start—a catalyst of sorts. He has about 50 acres of land set aside through USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program—which pays farmers to give their land a rest—and he says ever since he received the pollinator-focused certification he has seen his property through fresh eyes.

Before, Swanson says, he saw that land primarily as valuable because the plants growing on it kept his soil from eroding. Now, he adds, “I see that it provides not just pollinator habitat, but wildlife, birds—of all kinds of critters like to hang out in there! And I think that’s one of the big benefits of doing a certification like this; you start to look at property as an ecosystem rather than just a property.”

Twilight Greenaway is Civil Eats’ senior editor and former managing editor. Her articles about food and farming have appeared in The New York Times, NPR.org, The Guardian, Food and Wine, Gastronomica, and Grist, among other. See more at TwilightGreenaway.com. Follow her on Twitter. Read more >

Cinnamon Janzer is a Minneapolis-based freelance journalist with a focus on lesser-told stories on a mission to change how the world sees the Midwest. Her work has appeared in the Guardian, National Geographic, New York magazine, the Washington Post, U.S. News & World Report, Rewire.news, Fast Company, Eater Twin Cities, USA Today’s Go Escape magazine, and more. Read more >