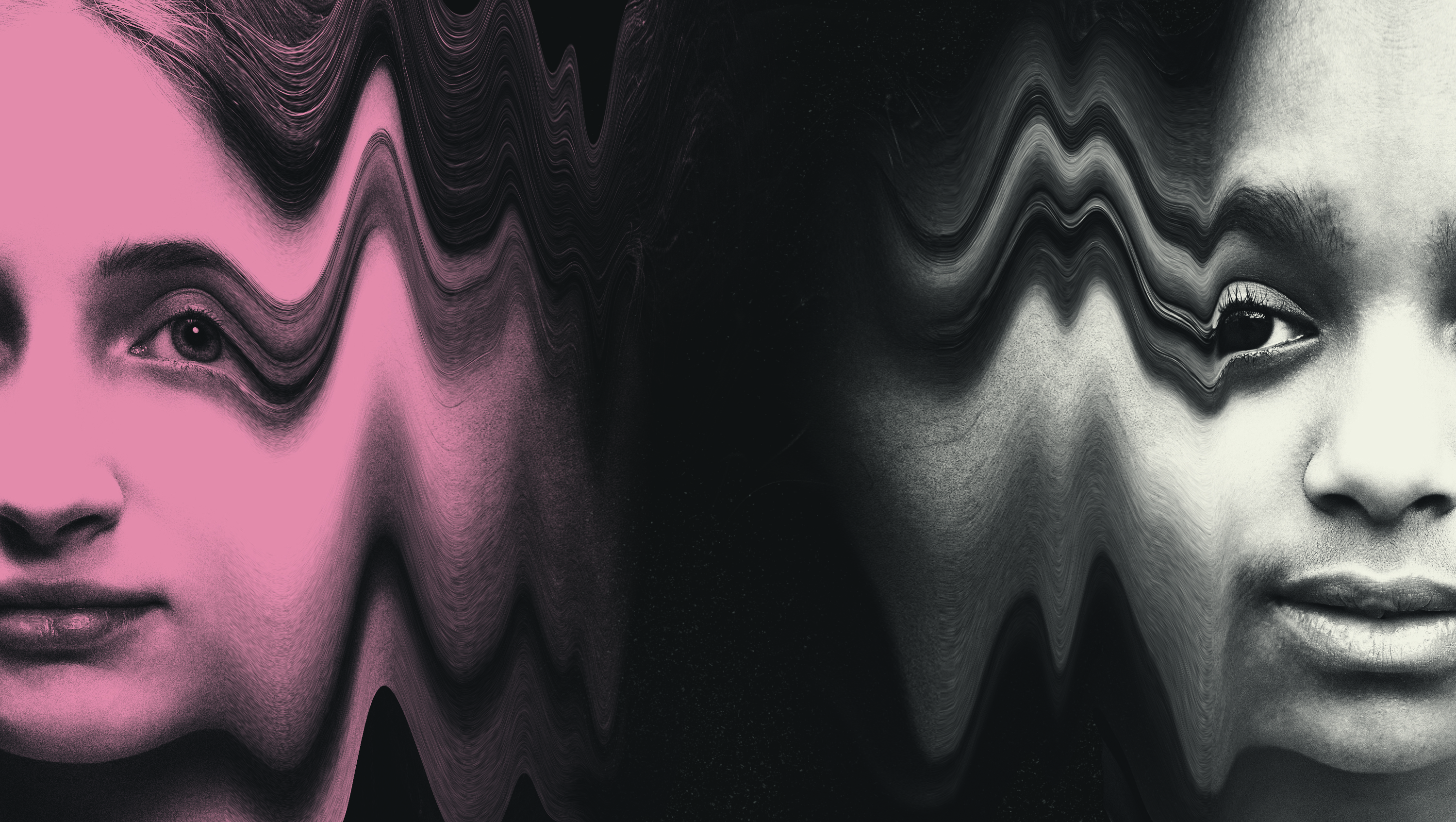

The most widespread use of augmented reality isn’t in gaming: it’s the face filters on social media. The result? A mass experiment on girls and young women. Joan Wongby

Joan Wongby

Veronica started using filters to edit pictures of herself on social media when she was 14 years old. She remembers everyone in her middle school being excited by the technology when it became available, and they had fun playing with it. “It was kind of a joke,” she says. “People weren’t trying to look good when they used the filters.”

But her younger sister, Sophia, who was a fifth grader at the time, disagrees. “I definitely was—me and my friends definitely were,” she says. “Twelve-year-old girls having access to something that makes you not look like you’re 12? Like, that’s the coolest thing ever. You feel so pretty.”

When augmented-reality face filters first appeared on social media, they were a gimmick. They allowed users to play a kind of virtual dress-up: change your face to look like an animal, or suddenly grow a mustache, for example.

Podcast: In the AI of the Beholder

Computers are ranking the way people look—and the results are influencing the things we do, the posts we see, and the way we think.

Today, though, more and more young people—and especially teenage girls—are using filters that “beautify” their appearance and promise to deliver model-esque looks by sharpening, shrinking, enhancing, and recoloring their faces and bodies. Veronica and Sophia are both avid users of Snapchat, Instagram, and TikTok, where these filters are popular with millions of people.

“The beauty filter sort of changes certain things about your appearance and can fix certain parts of you.”

Through swipes and clicks, the array of face filters enable them to adjust their own image, and even sift through different identities, with new ease and flexibility.

Veronica, now 19, scrolls back to check pictures from the time on her iPhone. “Wait,” she says, stopping on one. “Oh yeah … I was definitely trying to look good.” She shows me a picture of a glammed-up version of herself. She looks seductive. Her eyes are wide, lips slightly parted, and her skin looks tanned and airbrushed. “That’s me when I’m 14,” Veronica says. She seems distressed by the picture. Still, she says, she’s using filters almost every day.

“When I’m going to use a face filter, it’s because there are certain things that I want to look different,” she explains. “So if I’m not wearing makeup or if I think I don’t necessarily look my best, the beauty filter sort of changes certain things about your appearance and can fix certain parts of you.”

The face filters that have become commonplace across social media are perhaps the most widespread use of augmented reality. Researchers don’t yet understand the impact that sustained use of augmented reality may have, but they do know there are real risks—and with face filters, young girls are the ones taking that risk. They are subjects in an experiment that will show how the technology changes the way we form our identities, represent ourselves, and relate to others. And it’s all happening without much oversight.

The rise of selfie culture

Beauty filters are essentially automated photo editing tools that use artificial intelligence and computer vision to detect facial features and change them.

They use computer vision to interpret the things the camera sees, and tweak them according to rules set by the filters’ creator. A computer detects a face and then overlays an invisible facial template consisting of dozens of dots, creating a sort of topographic mesh. Once that has been built, a universe of fantastical graphics can be attached to the mesh. The result can be anything from changing eye colors to planting devil horns on a person’s head.

Computers are ranking the way people look—and the results are influencing the things we do, the posts we see, and the way we think.

These real-time video filters are a recent advance, but beauty filters more broadly are an extension of the decades-old selfie phenomenon. The movement is rooted in Japanese “kawaii” culture, which obsesses over (typically girly) cuteness, and it developed when purikura—photo booths that allowed customers to decorate self-portraits—became staples in Japanese video arcades in the mid-1990s. In May of 1999, Japanese electronics manufacturer Kyocera released the first mobile phone with a front-facing camera, and selfies started to break out to the mainstream.

The rise of MySpace and Facebook internationalized selfies in the early 2000s, and the launch of Snapchat in 2011 marked the beginning of the iteration that we see today. The app offered quick messaging through pictures, and the selfie was an ideal medium for visually communicating one’s reactions, feelings, and moods. In 2013, Oxford Dictionaries selected “selfie” as the word of the year, and by 2015 Snapchat had acquired the Ukrainian company Looksery and released the “Lenses” feature, much to the delight of Veronica’s middle school clique.

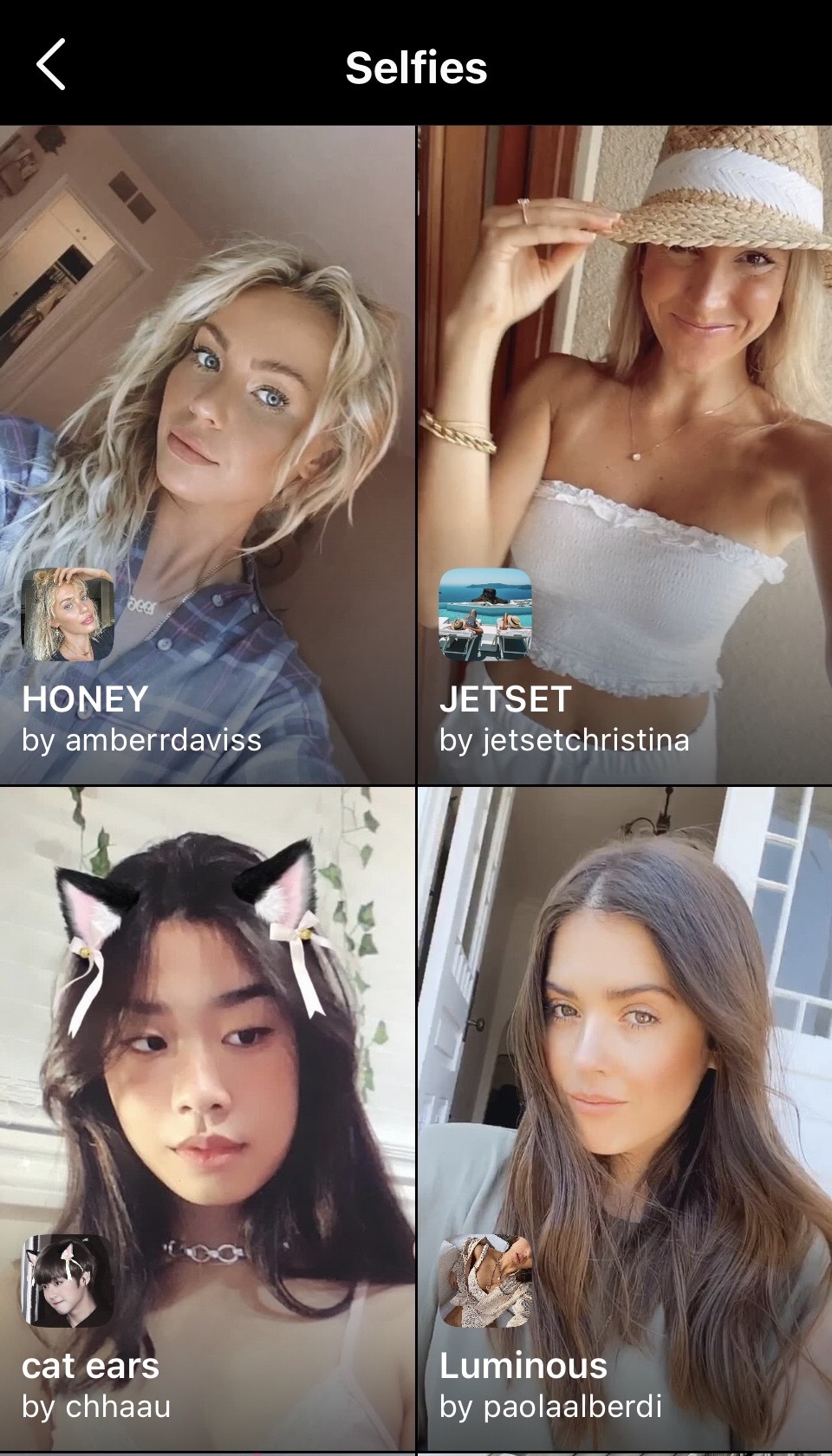

Filters are now common across social media, though they take different forms. Instagram bundles beauty filters with its other augmented-reality facial filters, like those that add a dog’s ears and tongue to a person’s face. Snapchat offers a gallery of filters where users can swipe through beauty-enhancing effects on their selfie camera. TikTok’s beauty filter, meanwhile, is part of a setting called “Enhance,” where users can enable a standard beautification on any subject.

And they are incredibly popular. Facebook and Instagram alone claim that over 600 million people have used at least one of the AR effects associated with the company’s products: a spokesperson said that beauty filters are a “popular category” of effects but would not elaborate further. Today, according to Bloomberg, almosta fifth of Facebook’s employees—about 10,000 people— are working on AR or VR products, andMark Zuckerberg recently told The Information, “I think it really makes sense for us to invest deeply to help shape what I think is going to be the next major computing platform, this combination of augmented and virtual reality.”

They are subjects in an experiment that will show how the technology changes the way we form our identities, represent ourselves, and relate to others.

Snapchat boasts its own stunning numbers. A spokesperson said that “200 million daily active users play with or view Lenses every day to transform the way they look, augment the world around them, play games, and learn about the world,” adding that more than 90% of young people in the US, France, and the UK use the company’s AR products.

Another measure of popularity might be how many filters exist. The majority of filters on Facebook’s various products are created by third-party users, and in the first year its tools were available, more than 400,000 creators released a total of over 1.2 million effects. By September 2020, more than 150 creator accounts had each passed the milestone of 1 billion views.

Face filters on social media might seem technologically unimpressive compared with some other uses of AR, but Jeremy Bailenson, the founding director of Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab, says the real-time puppy filters are actually quite a technological feat.

“It’s hard to do that technically,” he says. But thanks to neural networks, AI can now help achieve the kind of data processing required for real-time video altering. And the way it’s taken off in recent years surprises even longtime researchers like him.

A “beautiful” community

Many people enjoy filters and lenses—both as users and creators. Caroline Rocha, a makeup artist and photographer, says that social media filters—and Instagram’s in particular—provided her a lifeline at a crucial moment. In 2018, she was at a personal low point: someone very dear to her had died, and then she suffered a stroke that resulted in temporary paralysis of her leg and permanent paralysis of her hand. Things got so overwhelming that she attempted suicide.

“I just wanted to come out of my reality,” she says. “My reality was dark. It was deep. I passed my days inside four walls.” Filters felt like a breakthrough. They gave her “the chance to travel … to experiment, to try on makeup, to try a piece of jewelry,” she says. “It opened a big window for me.”

She had studied art history in school, and Instagram filters felt like a deeply human and artistic world, full of opportunity and connection. She became friends with AR creators whose aesthetic spoke to her. Through that, she became a “filters influencer,” though she says she hates that term: she would try different filters and critique them for a growing audience of followers. Eventually, she started creating filters herself.

Rocha became connected with creators likeMarc Wakefield, an artist and AR designer who specializes in dark, fantastical effects. (One of his hits is “Hole in the Head,” in which a see-through hole replaces the subject’s face.) The community was “so close and so helpful,” she says—“beautiful,” even. She had no technical expertise when she started creating AR effects, and spent hours poring over help documents with help from others.

Her first viral filter was called “Alive”: it overlaid the electrical pulse of a heartbeat right across the face of its subject. After a moment, the line distorts into a heart that encircles one eye before flashes of colored light illuminate the screen. Rocha says Alive was an homage to her own story of mental illness.

Rocha’s experience is not unusual: many people enjoy the playfulness of the technology. Facebook describes AR effects as a way to “make any moment more fun to share,” while Snapchat says the goal of Lens “is to provide fun and playful creative effects that allow our community to express themselves freely.”

But Rocha has changed her view. This artistic conception of filters now seems idealistic to her, not least because it is not necessarily representative of how the majority of people use filters. Artistic or funny filters may be popular, but they are dwarfed by beauty filters.

Life online for women is toxic and filled with hate and sexism. Some activists say it’s time to reimagine how the whole thing works.

Facebook and Snapchat were both hesitant to provide any data breaking out filters that are solely appearance enhancing from those that are more novel. Facebook’s creators categorize their own filters into 17 ambiguous buckets, whose names include “Appearance,” “Selfies,” “Moods,” and “Camera styles.” “Appearance” is in the top 10 most popular categories, said the Facebook spokesperson, but refused to elaborate further.

Rocha says she sees many women on social media using filters nonstop. “They refuse to be seen without these filters, because in their mind they think that they look like that,” she says. “It became, for me, a bit sick.”

In fact, she struggled with it herself. “I’ve always fought against this kind of fakeness,” she says, but “I’d say, ‘Okay, I have to change my picture. I have to make my nose thinner and give myself a big lip because I feel ugly.’ And I was like, ‘Whoa, Whoa, no, I’m not like that. I want to feel beautiful without changing these things.’”

She says the beauty-obsessed culture of AR filters has become increasingly disappointing: “It has changed because, in my point of view … the new generation of creators just want money and fame.”

“There is a bad mood in the community,” she says. “It’s all about fame and number of followers, and I think it’s sad, because we are making art, and it’s about our emotions … It’s very sad what’s happening right now.”

“I don’t think it’s just filtering your actual image. It’s filtering your whole life.”

Veronica, the teenager, sees the same patterns. “If someone is completely portraying themselves in one filter and has only posted photos in a filter meeting all of the beauty standards and gaining followers and making money off of the beauty standard that we have right now—I don’t know if that’s, like, genius or if that’s terrible,” she says.

Claire Pescott is a researcher at the University of South Wales who studies the behavior of preteens on social media. In focus groups, she’s observed a gender difference when it comes to filters. “All of the boys said, ‘These are really fun. I like to put on these funny ears, I like to share them with my friends and we have a laugh,’” she says. Young girls, however, see AR filters primarily as a tool for beautification: “[The girls] were all saying things like, ‘I put this filter on because I have flawless skin. It takes away my scars and spots.’ And these were children of 10 and 11.”

“I don’t think it’s just filtering your actual image,” she says. “It’s filtering your whole life.”

And this change is only just beginning. AR filters on social media are part of a rapidly growing suite of automated digital beauty technologies. The app Facetune has been downloaded over 60 million times and exists simply for easy video and photo editing.Presets are a recent phenomenon in which creators—and established influencers in particular—create and sell custom filters in Adobe Lightroom. Even Zoom has a “touch up my appearance” feature that gives the appearance of smoother skin in video calls. Many have heralded the option to buff your appearance as a low-effort savior during the pandemic.

Reality distortion field

During our conversations, I asked Veronica to define what an “Instagram Face” looks like. She replied quickly and confidently: “Small nose, big eyes, clear skin, big lips.”

This aesthetic relies on categories of AR effects called “deformation” and “face distortion.” As opposed to the Zoom-like touch-up that simply blends skin tones or saturates eye color, distortion effects allow creators to easily change the shape and size of certain facial features, creating things like a “bigger lip,” a “lifted eyebrow,” or a “narrower jaw,” according to Rocha.

Teenagers Sophia and Veronica say they prefer distortion filters. One of Sophia’s favorites makes her look like singer and influencer Madison Beer. “It has these massive lashes that make my eyes look beautiful. My lips triple in size and my nose is tinier,” she says. But she’s cautious: “Nobody looks like that unless you are Madison Beer or someone who has a really, really good nose job.”

Veronica’s “ideal” filter, meanwhile, is a distortion filter called Naomi Beauty on Snapchat, which she says all her friends use. “It is one of the top filters for two reasons,” she says. “It clears your skin and it makes your eyes huge.”

There are thousands of distortion filters available on major social platforms, with names like La Belle, Natural Beauty, and Boss Babe. Even the goofy Big Mouth on Snapchat, one of social media’s most popular filters, is made with distortion effects.

In October 2019, Facebook banned distortion effects because of “public debate about potential negative impact.” Awareness of body dysmorphia was rising, and a filter calledFixMe, which allowed users to mark up their faces as a cosmetic surgeon might, had sparked a surge of criticism for encouraging plastic surgery. But in August 2020, the effects were re-released with a new policy banning filters that explicitly promoted surgery. Effects that resize facial features, however, are still allowed. (When asked about the decision, a spokesperson directed me toFacebook’s press release from that time.)

When the effects were re-released, Rocha decided to take a stand and began posting condemnations of body shaming online. She committed to stop using deformation effects herself unless they are clearly humorous or dramatic rather than beautifying and says she didn’t want to “be responsible” for the harmful effects some filters were having on women: some, she says, have looked into getting plastic surgery that makes them look like their filtered self.

“I wish I was wearing a filter right now”

Krista Crotty is a clinical education specialist at the Emily Program, a leading center on eating disorders and mental health based in St. Paul, Minnesota. Much of her job over the past five years has focused on educating patients about how to consume media in a healthier way. She says that when patients present themselves differently online and in person, she sees an increase in anxiety. “People are putting up information about themselves—whether it’s size, shape, weight, whatever—that isn’t anything like what they actually look like,” she says. “In between that authentic self and digital self lives a lot of anxiety, because it’s not who you really are. You don’t look like the photos that have been filtered.”

“There’s just somewhat of a validation when you’re meeting that standard, even if it’s only for a picture.”

For young people, who are still working out who they are, navigating between a digital and authentic self can be particularly complicated, and it’s not clear what the long-term consequences will be.

“Identity online is kind of like an artifact, almost,” says Claire Pescott, the researcher from the University of South Wales. “It’s a kind of projected image of yourself.”

Pescott’s observations of children have led her to conclude that filters can have a positive impact on them. “They can kind of try out different personas,” she explains. “They have these ‘of the moment’ identities that they could change, and they can evolve with different groups.”

But she doubts that all young people are able to understand how filters affect their sense of self. And she’s concerned about the way social media platforms grant immediate validation and feedback in the form of likes and comments. Young girls, she says, have particular difficulty differentiating between filtered photos and ordinary ones.

Pescott’s research also revealed that while children are now often taught about online behavior, they receive “very little education” about filters. Their safety training “was linked to overt physical dangers of social media, not the emotional, more nuanced side of social media,” she says, “which I think is more dangerous.”

Bailenson expects that we can learn about some of these emotional unknowns from established VR research. In virtual environments, people’s behavior changes with the physical characteristics of their avatar, a phenomenon called the Proteus effect. Bailenson found, for example, that people who had taller avatars were more likely to behave confidently than those with shorter avatars. “We know that visual representations of the self, when used in a meaningful way during social interactions, do change our attitudes and behaviors,” he says.

But sometimes those actions can play on stereotypes. A well-known study from 1988 found that athletes who wore black uniforms were more aggressive and violent while playing sports than those wearing white uniforms. And this translates to the digital world: one recent study showed that video game players who used avatars of the opposite sex actually behaved in a way that was gender stereotypical.

Bailenson says we should expect to see similar behavior on social media as people adopt masks based on filtered versions of their own faces, rather than entirely different characters. “The world of filtered video, in my opinion—and we haven’t tested this yet—is going to behave very similarly to the world of filtered avatars,” he says.

Selfie regulation

Considering the power and pervasiveness of filters, there is very little hard research about their impact—and even fewer guardrails around their use.

I asked Bailenson, who is the father of two young girls, how he thinks about his daughters’ use of AR filters. “It’s a real tough one,” he says, “because it goes against everything that we’re taught in all of our basic cartoons, which is ‘Be yourself.’”

Bailenson also says that playful use is different from real-time, constant augmentation of ourselves, and understanding what these different contexts mean for kids is important.

“Even though we know it’s not real… We still have that aspiration to look that way.”

What few regulations and restrictions there are on filter use rely on companies to police themselves. Facebook’s filters, for example, have to go through an approval process that, according to the spokesperson, uses “a combination of human and automated systems to review effects as they are submitted for publishing.” They are reviewed for certain issues, such as hate speech or nudity, and users are also able to report filters, which then get manually reviewed.

The company says it consults regularly with expert groups, such as the National Eating Disorders Association and the JED Foundation, a mental-health nonprofit.

“We know people may feel pressure to look a certain way on social media, and we’re taking steps to address this across Instagram and Facebook,” said a statement from Instagram. “We know effects can play a role, so we ban ones that clearly promote eating disorders or that encourage potentially dangerous cosmetic surgery procedures… And we’re working on more products to help reduce the pressure people may feel on our platforms, like the option to hide like counts.” https://playlist.megaphone.fm/?e=MIT3184912056

Facebook and Snapchat also label filtered photos to show that they’ve been transformed—but it’s easy to get around the labels by simply applying the edits outside of the apps, or by downloading and reuploading a filtered photo.

Labeling might be important, but Pescott says she doesn’t think it will dramatically improve an unhealthy beauty culture online.

“I don’t know whether it would make a huge amount of difference, because I think it’s the fact we’re seeing it, even though we know it’s not real. We still have that aspiration to look that way,” she says. Instead, she believes that the images children are exposed to should be more diverse, more authentic, and less filtered.

There’s another concern, too, especially since the majority of users are very young: the amount of biometric data that TikTok, Snapchat and Facebook have collected through these filters. Though both Facebook and Snapchat say they do not use filter technology to collect personally identifiable data, a review of their privacy policies shows that they do indeed have the right to store data from the photographs and videos on the platforms. Snapchat’s policy says that snaps and chats are deleted from its servers once the message is opened or expires, but stories are stored longer. Instagram stores photo and video data as long as it wants or until the account is deleted; Instagram also collects data on what users see through its camera.

Meanwhile, these companies continue to concentrate on AR. In a speech made to investors in February 2021, Snapchat co-founder Evan Spiegel said “our camera is already capable of extraordinary things. But it is augmented reality that’s driving our future”, and the company is “doubling down” on augmented reality in 2021, calling the technology “a utility”.

And while both Facebook and Snapchat say that the facial detection systems behind filters don’t connect back to the identity of users, it’s worth remembering that Facebook’s smart photo tagging feature—which looks at your pictures and tries to identify people who might be in them—was one of the earliest large-scale commercial uses of facial recognition. And TikTok recently settled for $92 million in a lawsuit that alleged the company was misusing facial recognition for ad targeting. A spokesperson from Snapchat said “Snap’s Lens product does not collect any identifiable information about a user and we can’t use it to tie back to, or identify, individuals.”

And Facebook in particular sees facial recognition as part of it’s AR strategy. In a January 2021blog post titled “No Looking Back,” Andrew Bosworth, the head of Facebook Reality Labs, wrote: “It’s early days, but we’re intent on giving creators more to do in AR and with greater capabilities.” The company’s planned release of AR glasses is highly anticipated, and it has already teased the possible use of facial recognition as part of the product.

In light of all the effort it takes to navigate this complex world, Sophia and Veronica say they just wish they were better educated about beauty filters. Besides their parents, no one ever helped them make sense of it all. “You shouldn’t have to get a specific college degree to figure out that something could be unhealthy for you,” Veronica says.